The

Judson Legacy

Project

An Introduction to the Ministry and Mission of

Ann Hasseltine and Adoniram Judson, Jr.

[1]Originally published in A Noble Company: Biographical Essays on Notable Particular-Regular Baptists in America, Volume 8, Edited by Terry Wolever. (Springfield, MO: Particular Baptist Press, 2016), Pps 535-572, 626-632. Used with permission of Particular Baptist Press.

(Clossman Images will be noted by their number, ie, CI-0000.)

Adoniram Judson, Jr. was born the year George Washington was elected president of the United States. The new constitution for the United States of Americas had been debated, approved and was being implemented when the lad made his appearance on August 9, 1788, the first child of Adoniram Judson, Sr. and his wife, Abigail (nee Brown) Judson.

Washington became known as the Father of the United States of America. Adoniram Judson, Jr. became known as the father of the modern mission movement from America.

Over forty biographies have chronicled the life and ministry of Judson as he and his three wives launched the intentional movement of the gospel from the United States to the uttermost parts of the earth. Judson is, and should be, noted as the first foreign missionary from America. Though that status is sometimes debated, Judson’s influence on the modern mission movement cannot be questioned.

+++++++++++++++

Birth and early formation of Adoniram Judson, Jr.

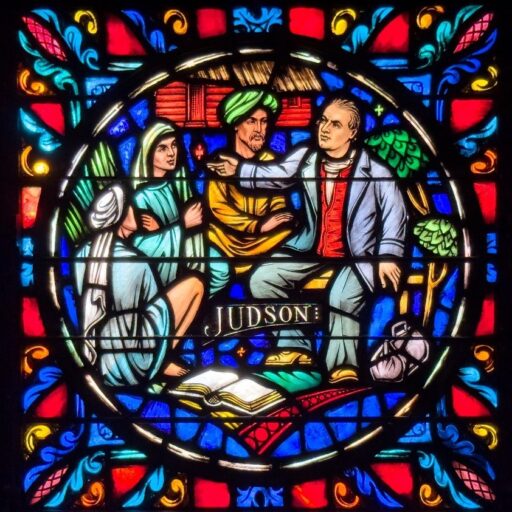

Adoniram Judson, Jr., in middle age.

Adoniram Judson, Jr. was born at the parsonage of a Congregational pastor in Malden, Massachusetts, the first of four children. He was named for his father, who carried the appellation of the biblical overseer of forced labor under kings Solomon and Rehoboam. Though his Hebrew name translates to “my lord is exalted,” that original Old Testament Adoniram was stoned to death when the Israelites revolted as reported in I Kings 5:13-14.

Judson, Sr. was a conservative Calvinistic minister and had high expectations of his namesake. The family moved from Malden to Wenham to Braintree and then to Plymouth during young Judson’s first 16 years. As he came of age in Massachusetts, Judson, Jr., saw the church from these four venues and through the theological lens of his father.

Mrs. Judson was a brilliant mother, fulfilling her role as pastor’s wife and caregiver with loyalty and finesse. She gave birth to a younger sister for Adoniram and named her Abigail (b. 1791), who would be a life-long friend and correspondent to her older, missionary brother. A third child, Elnathan, would grace the family in 1794 and provide a playmate for Adoniram during his formative years. Baby Mary Ellice was born in February of 1796, but passed away when only six months old. Her death made a big impact on Adoniram, who was eight years old at her passing.

To understand Judson, it is necessary to not only understand his domestic environment but also the world into which he was born. Baseball and soccer had not yet been invented, and thus adult leisure time was spent making bets on bull-baiting and bear-baiting. These blood sports were common past-times in the U.S. and Europe. The labor force during Judson’s early years was largely driven by slavery. Capitalism was growing in New England, but slavery and slave trading were common sights for the young pastor’s son.

In this new American nation, the largest crowds assembled were often for public hangings, an activity sponsored by government to sway elections, deter crime and create markets for local vendors and merchants. Occasionally, over 5,000 persons would gather at an announced location for the public execution of a local crook. Prostitution, child labor and alcoholism were rampant in America, just as they were in England. An avid reader, young Judson was aware of the state of the culture in his native New England.

Internationally the world was being divided up by European powers with regular wars over which nation would rule what part of the globe. Judson grew up hearing about the French Revolution and Napoleon. Spain and Portugal had divided up Central and South America. During Judson’s early years, Africa was the playground for many European nations, including France, Belgium, England, Italy, Portugal, Spain and even Germany. Britain controlled India and would eventually move into Burma.

Global colonialism was powered by commercial interests. When merchants got in trouble with nationals, government troops were called in to protect the economic interests of the colonizing nation. Thus, the early union of the commercial-military complex would be a factor influencing the world of young Judson as he grew to adulthood in the neighborhoods around Boston harbor.

Not only was Judson influenced by his family, his culture and world events, he was also impacted by the theological debates of the turn of the nineteenth century, which he heard from his father, the church and the education he experienced. Though Calvinism held sway for the past two hundred years, Arminianism was growing in the U.S. due to revivalism and individualism.[2] Primary in those discussions was the liberalization of the Congregational Church, which Judson, Sr., vocally opposed.

Originally composed of Puritans who wanted to purify the Church of England, the Congregational Church in America was formed to move away from the ritual and hierarchy of the Anglicans. In the American colonies it took Congregationalists about 150 years to become the establishment and take on many of the foibles of their English parentage.

Adoniram, Sr. attended Yale University, but later rejected the liberal tendencies of his alma mater. He was concerned about Unitarianism in the Congregational Church and was dismissed from his congregations in Malden (1791) and Wenham (1799) for expressing his beliefs too stridently. (The elder Adoniram would also be dismissed from the Plymouth congregation in 1817 when he changed his views on baptism, adopting the Baptist views of immersion of believers only.) Young Judson was aware of these discussions and was impacted by his father’s intransience (or courage) in theological debate.

+++++++++++++++

Judson’s conversion and the beginnings of the modern missionary movement from America

In 1804 Judson went to Providence and entered Rhode Island College at age 16 over the objections of his father. During the first year of his matriculation, the school changed its name to Brown University in appreciation of three brothers from the Brown family who gave the school financial stability.

During his second year at Brown, Judson embraced the teachings of Deism and with his roommate, Jacob Eames, regularly debated Deism versus Christian orthodoxy. Those debates covered such topics as the existence of heaven and/or hell, the existence of God and/or gods, the possibility of eternity, and life after death. At the 1807 graduation, Judson was recognized as valedictorian at age 19 and delivered the valedictory address. He had competed with Jacob Eames for this honor and won their academic competition during the last months of his classroom studies.

Successful in his undergraduate studies, fluent in Greek, Hebrew, and Latin, Judson returned to the Boston area and taught school for one year. During that time, he wrote two educational textbooks, but at age 20, found he did not have the personal discipline to maintain a classroom. He sold his school in the summer of 1808 and spent the next few months touring New England as far south as New York City, trying to determine the next chapter in his life.

During this perambulation, Judson stopped at an inn in Connecticut, securing a room adjacent to a guest who was ill. Since rooms in Connecticut inns in 1808 were defined by draperies or fabric suspended by a wire crossing the larger enclosure, Judson was able to hear the troubling sounds of the man and those ministering to him through the night. As he checked out the next morning, Judson inquired about his neighbor, only to learn that the man had died during the early morning hours. He also learned that the man’s name was Jacob Eames, his roommate and deist friend from Brown University.

“One single thought occupied his mind, and the words, Dead! lost! lost! were continually ringing in his ears. He knew the religion of the Bible to be true; he felt its truth; and he was in despair.”[3] In October of 1808, Judson enrolled as a special student at the recently established Andover Theological Seminary. “On the 2d of December, 1808, as he has recorded, he made a solemn dedication of himself to God. On the 28th of May, 1809, he made a public profession of religion, and joined the Third Congregational Church in Plymouth, of which his father was then pastor.”[4]

Judson was admitted to Andover Theological Seminary and because of his strong academic background, was permitted to bypass year one and begin the second year of the four-year program. The seminary was new and thus new methods and processes were at work in the administration and classrooms. Andover was formed as a conservative response to the more liberal seminaries in the Boston area, specifically Harvard, where the Unitarians had taken control. Judson’s father was one of the founders of Andover and thus, conservative Calvinistic theology and his dad were once again a part of young Judson’s life.

Several of “The Brethren” from Williams College, who were at the Haystack Prayer meeting of 1806, also enrolled at Andover. These five lads had taken refuge under a haystack during a rainstorm and after a time of prayer dedicated themselves to world missions. Upon their matriculation at Andover, they met Judson, who eventually became a member, and then leader, of this fraternity who had an interest in propagating the gospel in other cultures.

Samuel J. Mills, the original leader of the Brethren group from Williams College, is occasionally referred to as the father of American missions rather than Adoniram Judson, his colleague at Andover. Though an advocate of missions in many fields, Mills only spent two months as an overseas missionary.

Judson was also influenced at Andover by a published sermon entitled, A Star in the East (1809) by Claudius Buchanan, former chaplain to the British military in India. Buchanan suggested that every effort be undertaken to share the gospel with those in India who have never heard. Judson’s first introduction to Burma was probably through reading Michael Symes’ Embassy to Ava (1802), recounting the romantic adventures of a British diplomat assigned to engage the Burmese in trade.

The influence of William Carey (1761-1834), the true father of modern missions, who was living in the Danish colony of Serampore and working in the British colony of Calcutta, was a major motivating force for Judson. No accurate history of missions can be told without acknowledging this venerable saint of the gospel. The two ships that left with the first eight missionaries from America in 1812 were to rendezvous in Calcutta and receive orientation from Carey before deciding where to begin their missionary efforts.

These ideas from the Brethren, Buchanan, Symes and Carey were frothing in the mix at Andover Seminary during Judson’s time at Andover. Judson wrote in a letter years later:

It was during a solitary walk in the woods behind the college, while meditating and praying on the subject, and feeling half inclined to give it up, that the command of Christ, ‘Go into all the world and preach the Gospel to every creature,’ was presented to my mind with such clearness and power, that I came to a full decision, and though great difficulties appeared in my way, resolved to obey the command at all events.[5]

Judson and his Andover companions persuaded the Congregationalists to form in September 1810 the mother of all foreign mission societies in America, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. This Board dispatched Judson to England in January 1811 to see what ties could be established with William Carey’s sending agency, the London Missionary Society. In spite of a harrowing trip across the Atlantic, futile discussions with the London Missionary Society, and a reprimand from his American mission board, Judson remained undeterred in his call.

At the meeting of the board in Worcester, Massachusetts, on September 18, 1811, Judson, Samuel Nott, Jr., Samuel Newell, and Gordon Hall were appointed the first foreign missionaries from America. Their assignment was to “labor under the direction of this board in Asia, either in the Burman empire, or in Surat, or in Prince of Wales Island, or elsewhere, as, in the view of the Prudential Committee, Providence shall open the most favorable door.”[6]

+++++++++++++++

Judson’s marriage to Ann “Nancy” Hasseltine

At the September 1810 meeting of the Congregational Church, which formed the mission board that would eventually appoint Judson as a missionary, Adoniram and his colleagues were hosted for a meal in the home of Deacon John Hasseltine in Bradford. There, Judson met the deacon’s youngest daughter, Ann, and that casual acquaintance quickly grew into romance.

Judson asked father John Hasseltine for her hand in marriage using language that would prophecy their eventual relationship.

I have now to ask, whether you can consent to part with your daughter early next spring, to see her no more in this world; whether you can consent to her departure for a heathen land, and her subjection to the hardships and sufferings of a missionary life, ..to every kind of want, and distress; to degradation, insult, persecution, and perhaps a violent death. Can you consent to all this…for the sake of perishing, immortal souls; for the sake of Zion, and the glory of God?[7]

It is worth noting these young missionaries who had received a call from God and formed the first mission board, expected to leave the United States and never return. They saw their mission as a life-long commitment from which they could never renege. It might be comparable to modern twenty-somethings volunteering to go to Mars and do research, never expecting to return, but rather investing their lives in a cause which would be beneficial for others in the future.

CI-2621 of young Ann “Nancy” Hasseltine of Bradford, MA.

In March 1811, a Mrs. Norris died, leaving the Board of Commissioners $30,000[8] and by December 1811, other money started coming in to pull the trigger and launch these first foreign missionaries from America as soon as possible in 1812. Thus, on February 5, 1812, Ann Hasseltine and Adoniram Judson were wed in her home in Bradford, Massachusetts. The next day was the formal commissioning of the first missionaries from America.

+++++++++++++++

Commissioning and departure for India

News accounts say as many as two thousand people gathered at the Tabernacle Church in Salem, Massachusetts, on February 6, 1812, for the official service to set aside five young men “to the work of the gospel ministry, as missionaries to the heathen in Asia.” Three of these men were married, thus making the first foreign mission force a total of eight. Adoniram and Ann Judson, along with Samuel and Harriet Newell departed Salem on February 19th aboard the Caravan, following Samuel and Roxana Nott, Luther Rice, and Gordon Hall, who embarked from Philadelphia aboard the Harmony a day earlier.

These eight missionaries traveled aboard on two different ships. International tensions were growing between the United States and Britain and it looked like war was inevitable in 1812.

CI-2522. Commissioning of Adoniram Judson, Jr., Luther Rice, Samuel Nott, Samuel Newell and Gordon Hall. Note Ann Hasseltine Judson kneeling at the end of the pew with all eyes peering at her.

The odds of a ship getting to India to meet with William Carey’s mission was about 50%, and thus the American missionary party was split in two and disembarked from two different locations. It was truly a venture and an adventure in faith as the modern mission movement from America was birthed in the early years of the nineteenth century. The Caravan arrived in Calcutta on June 17th and the next day war was declared between the U.S. and Britain. The Harmony arrived at dock on July 8, 1812.

+++++++++++++++

Baptism and the Baptists

During their four-month journey from Massachusetts to Calcutta, India, the Judsons and Newells found several activities to occupy their time. The ship was about 97 feet long and was manned by 18 sailors. As a freighter, it was loaded with hemp, cotton, manufactured iron goods and other items merchants might purchase in India. The top deck was the grocery store with cattle, sheep, chickens, and pigs tied to the masts only to slowly dis- appear as the occupants needed three meals per day to sustain the trip.

Ann Judson and Harriet Newell were best friends, newlyweds, and enjoyed companionship talking about New England and making plans for their new life. Samuel and Adoniram had been in Andover Seminary together and continued conversations on theology and biblical subjects. To stay in shape physically, the four friends danced twice each day on the cramped deck of the Caravan next to the livestock.

Knowing that he would soon see William Carey, the Baptist missionary, face to face, Judson did a special study aboard the ship concerning baptism as reported in scripture and practiced by the church. The entire group of eight Congregational missionaries was pedobaptist, having been sprinkled as infants at the behest of their parents into their local Congregational parish. Soon they would have to face the Baptists who practiced baptism by immersion and immersed only believers.

Well into the four-month voyage to India, Judson had to admit the Baptists were right. He wrote, “that I, who was christened in infancy, on the faith of my parents, have never yet received Christian baptism.”[9] Onboard ship, Ann took the role of the pedobaptist’s advocate and tried to argue the “traditional” side of baptism only to see that her defenses were inadequate.

Upon arriving in Calcutta, the Judsons discussed their new understanding of baptism with William Carey and asked for immersion. Their formal believer’s immersion occurred on September 6, 1812, in Lal Bazar Baptist Chapel officiated by Carey’s assistant, William Ward. The next day, September 7th, Ann wrote a friend asking, “Can you, my dear Nancy, still love me, still desire to hear from me, when I tell you I have become a Baptist?”[10]

CI-2528. Lal Bazar Chapel, Calcutta, where Ann, Adoniram and Luther Rice were immersed to become Baptists in 1812.

The story intensified, however, when the Harmony arrived in Calcutta on July 8th and Luther Rice reported to Judson that he had debated believer’s baptism with English Baptists aboard his ship all the way to India. With no human communication between the Caravan and the Harmony for over four months, the Judsons and Rice came to the same theological conclusion. On November 1, 1812, Luther Rice was immersed and became a Baptist.

These three young adults were now Baptists and wrote the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions affirming their new understandings of baptism and resigned as missionaries under appointment. These three Baptists were now unemployed and evicted from India.

+++++++++++++++

In and out of India

Not only was theological transformation occurring, but the political scene was also in turmoil. The British East India Company did not want religious workers in India because these missionary-types taught laborers that all people are created in the image of God and are of great worth to God. For his own safety, William Carey had already departed English-controlled Calcutta and moved to Danish-controlled Serampore. The liberating ideals of evangelical Christianity had no place in the economic interests of the colonists, nor the British military sent to protect their western investment.

Evicted from Calcutta, these pioneer missionaries scrambled to find a permanent venue for ministry. Samuel and Roxana Nott and Gordon Hall ended up in Bombay where they found protection from the British East India Company and did a major work through an orphanage under the sponsorship of the Congregationalists. The Newells went to Mauritius, where Harriet died in childbirth, thus becoming the first death related to the modern mission movement from America. Widower Samuel Newell eventually did missionary work in Ceylon.

The three Baptists, who had resigned from the Congregational mission board, followed the Newells to Mauritius only to dispatch Luther Rice back to America to try to organize Baptist congregations to support the Judsons who were stranded. Rice departed with these words from Judson, “Should there be formed a Baptist society for the support of a mission in these parts, I should be ready to consider myself their missionary.”[11]

CI-2530 of ship Georgiana leaving India for Burma with the Judsons on board.

Undaunted, Adoniram Judson and his equally determined wife Ann, returned to India, this time to Madras, only to be evicted a second time. They could only find a ship going to Burma, a hostile and utterly unreached place. William Carey had told Judson in India a few months earlier not to go there. It probably would have been considered a closed country today—with anarchic despotism, fierce war with Siam, enemy raids, constant rebellion, no religious toleration. All the previous missionaries had died or left.[12]

Having no other options beyond deportation and jail, Ann and Adoniram ended up in Rangoon on July 13, 1813, a day annually celebrated by Christians in the modern nation of Myanmar. Though sick from having miscarried her first baby, Ann wrote, “The country presents a rich, beautiful appearance, everywhere covered with vegetation, and, if cultivated, would be one of the finest in the world.“[13]

+++++++++++++++

Initial mission strategies and successes of the Judsons

Late in life, Judson outlined the goals of his missionary career stating, “I used to think, when first contemplating a missionary life, that, if I should live to see the Bible translated and printed in some new language, and a church of one hundred members raise up on heathen ground, I should anticipate death with the peaceful feelings of old Simeon.”[14] To accomplish this goal, his strategy was to translate the Bible into the Burmese language—a major accomplishment since Burmese did not have a Western alphabet, but rather one based on a corruption of Pali. To the best of our knowledge, there was no one in the world who could speak and write both English and Burmese in 1813.

CI-2551. Adoniram Judson, Jr. baptizing his first convert to the Christian faith, Maung Nau, on June 27, 1819.

Language and culture. The Judsons moved into a missionary compound constructed by Felix Carey, oldest son of William Carey, who had attempted a mission to Burma before Judson arrived. A Buddhist monk was employed and Judson committed twelve hours each day to learning the language. In a letter to this friend Samuel Newell in Ceylon, he wrote, “Respecting our plans, we have at present but one—that of applying ourselves closely to the acquirement of the language, and to have as little to do with the Government as possible.”[15] The Burmese were a “reading people” and possessed an extensive literature. Judson already knew Greek, Hebrew and Latin and felt he would be most effective in Burma if he learned their language.

While Adoniram worked on linguistics, Ann learned conversational Burmese quickly just to establish their home. She built relationships with the wives of local political and civic leaders and developed connections that would help them survive in the future. She endeared herself to the wife of the viceroy for a very pragmatic reason—survival. “My only object in visiting her was, that, if we should get into any difficulty with the Burmans, I could have access to her, when perhaps it would not be possible for Mr.Judson to get access to the viceroy.”[16]

First publication. After three years, in July 1816, Judson finished his first tract in his new language and entitled it A View of the Christian Religion, in three parts, Historic, Didactic, and Preceptive. The three sections were, as indicated, historical (a quick run through the storyline of the Bible), didactic (the way of salvation, focusing on the work of Jesus), and preceptive (guidance on how to live and behave daily). This pamphlet, also entitled, The Way to Heaven, and always under revision, would be a mainstay of the Burmese mission for years. It is still in print today.

Three months later in October 1816, the first missionaries recruited by Luther Rice and assigned to Burma, George and Phoebe Hough, arrived in Rangoon. Hough was a printer whose skill would make Judson’s linguistic work available to the Burmese public. With the first tract ready to go public, a professional printer to manage the task, and a printing press gifted from English Baptists, Judson’s mission was ready. These early successes were tempered by constant suffering from tropical diseases and grief over the death of their second child, Roger, who lived from September of 1815 until May of 1816.

Organizing the mission. The Judsons began their work in Burma with no endorsements and no financial support from the U.S. In essence, they united with the Burmese mission led by Felix Carey and lived in the Carey compound while it was empty. Felix and his family had moved to the capital city, Ava, hoping for better relations with government leaders. The wife and children of Felix Carey would later drown in a tragic accident on the Irrawaddy River, thus leaving the Rangoon compound permanently in the hands of Judson.

Luther Rice, however, had been successful guiding the Baptists to organize the General Missionary (or Triennial) Convention’s Board of Foreign Missions in March 1814. They selected the Judsons as their first missionary appointees. That good news reached Burma in September of that same year. The mission goals were simple as long as the team was only Adoniram and Ann, but now that Mr. and Mrs. Hough were on the field, more structure was required.

On November 7, 1816, Judson and Hough committed to these Articles of Agreement:

- We give ourselves to the Lord Jesus Christ, and to one another by the will of God.

- We agree to be kindly affectioned one towards another with brotherly love,…

- We agree in the opinion that our sole object on earth is to introduce the religion of Jesus Christ into the empire of Burmah;…

- We therefore agree to engage in no secular business for the purpose of individual emolument:…

- We agree to…place all money and property, from whatever quarter accruing, in the mission fund:…

- We agree that all the members of the mission family have claims on the mission fund for equal support…

- We agree to educate our children with a particular reference to the object of the mission;…

- All appropriations from the mission fund shall be made by a majority of the missionary brethren united in this compact;[17]

One week later, November 14, 1816, Judson responded to Rice with this classic description of the ideal missionary candidate:

Encouraging other young men to come out as missionaries, do use the greatest caution. One strong headed conscientiously obstinate fellow would ruin us. Humble, quiet, persevering men, men of sound, sterling talents (though perhaps not brilliant), of decent accomplishments, and some natural aptitude to acquire a language; men of amiable, yielding temper, willing to take the lowest place, to be the least of all and the servants of all; men who enjoy much closet religion, who live near to God, and are willing to suffer all things for Christ’s sake, without being proud of it, these are the men.[18]

In September of 1818, two other missionary families were appointed by the Baptists to join the Judsons and Houghs. Edward and Eliza Wheelock, plus James and Elizabeth Colman, all from Boston, were affirmed by the Baptists at their 1817 meeting and arrived the next year in Rangoon, bringing the total number of missionaries to eight.

First building—the zayat. By 1819, Judson felt enough confidence in his language skills to go public orally. He constructed a zayat, a gazebo-type covered platform used by Buddhist monks for teaching, on the main road to the Shwe Dagon Pagoda. The zayat was four feet off the ground with dimensions of 27 feet by 18 feet. Judson’s daily routine was to sit in the outward veranda section and call out in Burmese to people passing by, “Ho! Everyone that thirsteth.” Like the neighboring Buddhist monks in their zayats, Judson hoped to engage someone in conversation about “the one Being who exists eternally and who is exempt from sickness, old age, and death….”[19] Many random conversations about the existence of a Deity were held on that veranda with Burmans who denied the existence of any deity.

CI-2548. Judson’s first Zayat where he held Christian worship and invited inquirers for instruction in the Christin faith.

The middle section of the building was for Sunday worship, but also served as Judson’s office and workspace for translating scripture. The back section was an entryway that bordered on the mission compound and surrounding gardens. The first public Christian worship ever held in Burmese was conducted on April 4, 1819. Judson wrote in his journal, “The congregation today consisted of fifteen persons only besides children. Much disorder and inattention prevailed…”[20]

First baptism. Judson baptized the first Burmese convert on July 1819, seven and a half years after leaving America, six years after landing in Burma and three months after preaching his first public sermon. Though Judson had distributed tracts and engaged in conversations about Christianity, few people had expressed interest. The first inquirer had surfaced in March of 1817 by asking, “How long time will it take me to learn the religion of Jesus?”[21] The questioner did not follow through.

Maung Nau was about 30 years old when he declared himself a disciple of Christ. After a month of intense instruction, Maung Nau wrote his profession of faith declaring, “I believe that the divine Son, Jesus Christ, suffered death, in the place of men, to atone for their sins”[22] and asked for baptism. On Sunday, June 27th, the gathered worshippers “proceeded to a large pond in the vicinity the bank of which is graced with an enormous image of Gaudama, and there administered baptism to the first Burman convert.”[23] Maung Nau would become a beloved Christian leader in the early church in Burma. A large and active congregation in Yangon now bears his name. Two additional converts would be baptized later in that same summer.

+++++++++++++++

Struggles of the Judsons in their missionary work

Ann to England and America. Tropical disease was always a struggle for the early missionaries and the Judsons were frequent victims of those molds, germs and viruses. By 1821, Ann had lost two children and was failing herself because of liver problems. She left Burma on August 21, 1821, to return to the west for treatment, leaving Adoniram and the Colmans in Rangoon with Hough printing from Calcutta.

Her ship docked in England where she was befriended by Joseph Butterworth (1770-1826), a member of parliament and a wealthy bookseller. Butterworth was a colleague of William Wilberforce and also served as treasurer for the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society. Ann’s third child would be named Maria Elizabeth Butterworth Judson in honor of this philanthropist who assisted the Judsons and helped form the British and Foreign Bible Society. Butterworth also published Ann Judson’s book, A Particular Relation of the American Baptist Mission to the Burman Empire.[24]

In September 1822, Ann arrived in the U.S. and was feted as a celebrity. Through the work of Luther Rice, the story of the Judsons had taken root and spread throughout America. During this time of recuperation, Ann wrote A Particular Relation of the American Baptist Mission to the Burman Empire (1823) and the book became a bestseller. It helped advance the cause of missions and made Judson a household name throughout the United States.

CI-2570. Judson’s arrest on suspicion of being an agent for the British who had invaded Burma.

While in the States, Ann learned how to administer inoculations for chicken pox from Adoniram’s brother, Elnathan, who was a physician in Baltimore. This medical knowledge would be helpful to the missionaries when epidemics ran their course through the Burmese population. Ann returned to Rangoon December 5, 1823, accompanied by newly-appointed missionaries, Jonathan and Deborah Wade. She and Adoniram moved their work to Ava because the emperor had given them land and invited the missionaries to the capital city.

The first ten years of missionary work were invested in building an infrastructure for future efforts. Language considerations were primary followed by staffing, facilities, relationships, structures and work rules. The next ten years in Burma, however, would be marked by struggles dwarfing even those of the first ten years.

Disease and death. Continuity was necessary in effective missionary endeavors. Learning language and culture cannot be done in a year or even a decade as these pioneers would learn. Yet with the best of intentions, staffing beyond the Judsons would remain a problem.

- Though George Hough arrived in October 1816 he would evacuate to India in 1818, due to his fear of the government in Rangoon. For the next four years he worked from Calcutta, only to return to Burma in 1822.

- Edward Wheelock arrived in September 1818, but died in August 1819, while on his way to Bengal to treat a hemorrhage. His wife, Eliza, remarried and stayed in Calcutta.

- James Colman also arrived in September 1818, but died in July 1822, while trying to establish a missionary outpost in Chittagong. His widow, Elizabeth, married a missionary and stayed in the Indian state of Orissa.

- On December 13, 1821, Jonathan D. Price, M. D., arrived in Rangoon as the newest appointee of the Baptist mission board. His wife, Mary, died five months later. Dr. Price died in 1828.

The idealistic Western missionaries knew they would encounter diseases never seen in the West, but had no idea as to the extent of these struggles. Many diseases did not have names and few had remedies. Sanitation and germ theory had not yet been engaged. Hospital care and trained doctors were a thing of the future.

Ann and Adoniram Judson lost all three of their children to birthing complications or childhood diseases. Ann lasted thirteen years in Burma, but would eventually succumb to an unnamed fever in 1826. Adoniram lost most of his speaking voice by 1838 and eventually could preach only in a whisper. Tuberculosis, consumption, malaria, cholera, and other yet unnamed diseases were always on the mind of the early missionaries in Burma.

Government relations. During his early years in Burma, Adoniram Judson lived in limbo as to his formal relationship with the government and its representatives in Rangoon. The emperor’s capital was in Ava, or surrounding regions, and would be moved with each new regime. The commercial hub and largest city was Rangoon, where Judson spent the first eleven years of ministry (1813-1824).

The missionary always has the decision whether to address the message of the gospel to the leadership of the culture or to the poorest in the culture who scratch out an existence on the trash heap. While others may choose one of the other, Adoniram Judson pragmatically chose both. In her book Ann Judson reports that after visiting the Burmese viceroy’s wife in December 1814, “We intend to have as little to do with the government people as possible, as our usefulness will, probably, be among the common people.”[25] But circumstances compelled them to deal with the leaders also.

With no laws or precedents on church-state relations, Judson was at the whim of whoever was in charge in Ava. A change in religion could be perceived as treason against the nation and against the emperor, thus punishable by death. The emperor allowed non-Buddhist religious workers to lead worship for non-Burmese guests who might be in the country, but they were not to proselytize the locals who were expected to remain Buddhist to be truly Burmese.

Dr. Price’s medical successes, especially dealing with cataract surgery, resulted in an invitation to visit Ava and report to the emperor. Price and Judson made the trip, were received warmly and invited to move to the capitol city. Judson had previously been to Ava with Colman (December 1819-February 1820) asking for religious freedom, but was rebuffed. But now, due to the medical miracles of Dr. Price, the door was opening for more dialogue with the Buddhist national leadership. Price remained in Ava, while Judson hurried to Rangoon to fetch Ann and move to the capital.

With eighteen baptized members in the Rangoon church, the mission operation was left in the hands of Hough and Wade. Price and Judson moved to Ava, which, in reality, set up the team for the greatest struggle of their ministry—21 months of imprisonment in two different Burmese jails.

War and imprisonment. British colonialism sailed from India into Burma in June 1824, and the Burmese government responded.by imprisoning all seven Western men who were in the neighborhood around Ava. If one looked British, they were considered the enemy or spies for the enemy. Judson was brutally arrested in his new Ava home and moved to prison, where he suffered horribly at the hands of his captors.

CI-2578. While imprisoned, Judson was often forced to sleep at night on his shoulders with his feet elevated on a bamboo pole.

Prison guards in Ava were convicted murderers and thus able to abuse and beat prisoners at will. Judson, a fastidious dresser, found himself in the squalor of a prison environment from which he could not find relief. Along with his other Caucasian colleagues, he was often required to sleep with his feet tied to a bamboo pole above his head.

Daily fear of beatings that began each day at 3 p.m. was a part of the prison routine. Oppressive heat, incessant rains, permeating stench, diseased rodents, and unending din defined the prison experience. The Caucasians lived under the fear of the tradition they would be sacrificed to the gods to insure a Burmese victory. Not only did Judson live with the anticipation of torture and death, he lived daily with the shrieks of those going through such torture.

Afterwards, Judson did not talk much about his months of imprisonment, but once described his situation as “Illness nigh unto death, and three or five pairs of fetters to aid in weighing down the shattered and exhausted frame,…”[26] Five pairs of fetters weighed about 14 pounds and allowed him to take strides that were only heel to toe in length. Once he was forced to walk eight miles on a sharp, rocky road which lacerated his feet, attracting mosquitoes to his blood at night. His feet and ankles would be marred the rest of his life.

CI-2573. One of the daily visits of Ann and baby daughter, Maria, to bring food to Adoniram in prison.

Ann was a heroine during this time, because of her faithful service in bringing food and sustenance to her husband and other prisoners. She walked four miles daily to care for those Caucasians in the prison, providing food and health care necessities. She regularly sought to make the political leaders aware her husband was an American, not British, and thus should not be incarcerated. She used her household dishes and cutlery to bribe the guards to keep her husband alive. During this ordeal, Ann delivered a baby, the before-mentioned Maria Elizabeth Butterworth Judson, and took only 20 days off from caring for the prisoners. Her story during the prison months is truly courageous. As the war came to a climax with continual British victories, the Burmese government asked for negotiations. The candidate with the most knowledge of Western ways and the Burmese language was the prisoner, Adoniram Judson. Though still a captive, he was released from jail to negotiate the peace treaties and scribe the documents between the warring nations. Neither nation had been friendly to Judson. The British had expelled him twice from India and the Burmese had imprisoned him for the better part of two years, yet there was no malice in his peace conferencing. From Rangoon he wrote on March 25, 1826:

I long for the time when we shall be able to re-erect the standard of the gospel, and enjoy once more the stated worship and ordinances of the Lord’s house. I feel a strong desire henceforth to know nothing among this people, but Jesus Christ and him crucified; and under an abiding sense of the comparative worthlessness of all worldly things, to avoid every secular occupation, and all literary and scientifick pursuit, and devote the remainder of my days to the simple declaration of the all precious truths of the gospel of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ.[27]

After a short reunion with Ann and Maria, the mission, now consisting of the Judsons, the Boardmans, the Wades and four converts from the Rangoon church, moved from Ava to Amherst and Moulmain (sometimes spelled Maulmain) to live under the protection of the British flag. Judson reluctantly accepted a short-term translation job with the British authorities and returned to Ava for two months.

Ann remained in Amherst and “in the midst of her sacred toils she was smitten with fever. Her constitution undermined by the hardships and sufferings which she had endured, could not sustain the shock, and on October 24, 1826, in the 37th year of her age, she breathed her last.”[28] Just when it looked like normalcy might return, Ann Hasseltine Judson died. To compound Judson’s grief, six months later little Maria died and was laid to rest next to her mother under a hopia tree. Soon after, Judson learned of his father’s death in Massachusetts.

Depression. By 1826, 13 years after entering Burma, Judson had lost his wife and three children. He had spent 21 months in prison. The 18 members of his church were dispersed or dead. The accumulation of these tragedies drove Judson into a period of depression.

Leaving his missionary colleagues in Moulmain, the widowed Judson tried to reignite his Christian ministry in Rangoon and Prome, only to find harassment by the Burmese government too severe to be productive. He returned to Moulmain to live in the forest, contemplating his worth, his lack of success, and even his death. Missionary colleagues brought food and supplies to him in the tiger-infested jungle to sustain his life during his time in the valley of despair.

Judson destroyed all letters of commendation. He formally renounced the honorary Doctor of Divinity that Brown University had given him in 1823 by publishing a letter in the American Baptist Magazine. He gave all his private wealth (about $6,000) to the Baptist Board. He asked that his salary be reduced by one quarter and promised to give more to missions himself. In October 1828, he built a hut in the jungle some distance from the Moulmain mission house and moved in on October 24th, the second anniversary of Ann’s death, to live in total isolation.[29]

Clossman image 2592 expresses Judson’s desolation in his hut in the jungle.

Judson had a grave dug beside his jungle hut and sat beside it contemplating the stages of the body’s dissolution. He pressured his sister, Abigail, to see that all his letters in New England were destroyed. He retreated for forty days further into the tiger-infested jungle and wrote in one letter than he felt utter spiritual desolation. “God is to me the Great Unknown. I believe in him, but I find him not.”[30] Yet, in his despair he continued to translate the Old Testament into Burmese 25 verses per day.

+++++++++++++++

Lasting successes for Adoniram Judson and the modern missionary movement from America

But the tide was turning is small ways and the mission started seeing some evidences of success. Moving the mission to Moulmain relieved the tension that Judson had felt for 13 years, trying to determine his position with the Burmese government. He could now live and work under the rule of the British government. By 1826, the British East India Company had reversed its policy and began to welcome missionaries to their colonial boundaries. Laws had passed through the British parliament in 1833, pushed by Joseph Butterworth, William Wilberforce and the Clapham Society, that abolished slavery in the British Empire.

Mission leadership. The Triennial Convention’s Board for Foreign Missions dispatched outstanding missionary colleagues to assist Judson in the Burmese effort. Chief among these were George and Sarah Boardman, Jonathan and Deborah Wade, Cephas and Stella Bennett, and other like-minded Christians. Boardman led the nascent mission in Tavoy, south of Moulmain, and found significant success among the Karens. These animistic people had a legend expecting a white man to come from a ship bringing a book and tell them about the future. When Boardman arrived with a Bible, the Karen expectations were fulfilled.

CI-2607. Judson prays and thanks God upon the completion of the Bible translation into Burmese, January 31, 1834.

One of his early converts, Ko Tha Byu, would become an early and effective evangelist to his own Karen people. Trained by Boardman and Wade, Ko Tha Byu would baptize hundreds and become a major force drawing the majority of his tribe to Christianity. Boardman died February 11, 1831, while on a trip to the hills east of Tavoy to baptize new converts. The Karens had no books and no written language when they encountered the American missionaries. Jonathan Wade codified the Karen language and translated the Bible for their use. One of the earliest settlements northeast of Tavoy was named Wadesville in his honor.[31]

Annual reports. Out from under the stifling influence of the Burmese government and with the new-found interest from the Karens, the 1831 report from the Burman Mission told of 217 baptisms compared to 18 baptisms in the first four years (1819- 1822) in Rangoon. Of these baptisms, 136 were at Maulmain, 76 at Tavoy and five in Rangoon. Two million pages of tracts and translations of Scripture had been printed. New missionary couples had arrived, with Mr. and Mrs. Mason going to Tavoy, Mr. and Mrs. Jones to Rangoon (and eventually to Bangkok, Siam), and Mr. and Mrs. Kincaid to Maulmain (and eventually to Rangoon, Ava and Prome).[32]

The 1832 report included one hundred forty-three baptisms, with three in Rangoon, seventy in Maulmain, sixty-seven in Tavoy, and three at Mergui. Judson noted that five hundred sixteen had been baptized since he arrived in Burma and only seventeen had been excluded from the church.[33] The darkness was lifting.

Printing and publishing. The mission’s increasing fluency in the Burmese language and culture was maturing by 1830, and thus scripture translations and tracts were printed more frequently and more professionally. Leading the printing arm of the mission was Cephas Bennett, replacing George H. Hough, who resigned to accept a position with the British government. “The total number of pages printed from 1830 till 1864, when Mr. Bennett retired, was 164,208,137. Distribution reached a peak in 1836, when 10,380,956 pages were issued.”[34]

Indigenous leadership. From his earliest days, Judson wanted the Burmese church to have indigenous leadership and took every opportunity to provide such training to new converts. He was especially good at mentoring and modeling. “Mr. Judson’s magnetism of character held his assistants to him with hooks of steel. He had the gift of getting work, and their best work, out of the converted natives. Promising boys and young men he took under his own instruction and qualified them to become teachers and ministers.”[35] Judson wrote in 1835,

My ideas of a seminary are very different from those of many persons. I am really unwilling to place young men, that have just begun to love the Saviour, under teachers who will strive to carry them through a long course of study….I want to see our young disciples thoroughly acquainted with the Bible from beginning to end, and with geography and history, so far as necessary to understand the Scriptures….I would also have them carried through a course of systemic theology,…And I would have them well instructed in the art of communicating their ideas intelligibly and acceptably by word and by writing.[36]

CI-2631. A Karen couple who were among the earliest converts to accept the Christian message.

Other mission groups were arriving in the East and were teaching English to help the locals become better citizens of the British Empire, rather than citizens of the Kingdom of God. Judson wrote “that English preaching, English teaching, and English periodicals are the bane of missions in the East. There are several missionaries—more, it is true, from Great Britain than from America—who never acquire the languages, except a mere smattering of them.”[37]

Bible translation. The year 1834 would prove to be pivotal for Judson and the course of the mission. On January 31st of that year, Judson finished translating the Bible into Burmese. He knelt at his desk in Moulmain and dedicated the document to God. “May He make His own inspired word, now complete in the Burman tongue, the grand instrument of filling all Burmah with songs of praise to our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen.”[38]

But the Bible would not be printed in its entirety for another ten years, due to constant revisions made by Judson and his team. The main body of work was finished. Judson, however, had doubts as to the necessity of printing the entire bulky edition of his translation, thinking it was too off-putting to the Burmese reader and would cause more confusion than help.

The translation of the Bible was completed due to Judson’s dogged determination to fulfill the commitment he had made to put the Scripture into the Burmese language. In the midst of his depression, he dutifully translated 25-30 verses each day whether he felt like it or not. He stubbornly battled against his despondency and worked diligently to fulfill his pledge.

This translation remains the standard for Christians in Myanmar today. A committee convened in 1964 to update and modernize Judson’s work, disbanded after determining there were no improvements to polish the translation work of Adoniram Judson’s Burmese Bible.

+++++++++++++++

Marriage to Sarah Hall Boardman

Three months later, April 10, 1834, Judson’s journal reads:

Was married to Mrs. Sarah H. Boardman, who was born at Alstead, New Hampshire, November 4, 1803, the eldest daughter of Ralph and Abiah O. Hall—married to George D. Boardman, July 4, 1825—left a widow February 11, 1831, with one surviving child, George D. Boardman, born August 18, 1828.[39]

With that simple journal entry, a new chapter began for Adoniram Judson. He had been single for nearly seven and a half years and Sarah for three years when they decided to marry after a four-day courtship. Unlike other widowed missionaries, Sarah Boardman had stayed in Burma to fulfill her missionary calling.[40] Sarah Hall Boardman was a linguistic match for Judson, having become proficient in several languages. She translated Pilgrim’s Progress into Burmese and translated the entire New Testament in Peguan. As the guiding spirit of the mission at Tavoy after George Boardman’s death, the British government stipulated throughout their provinces that schools should be “conducted on the plan of Mrs. Boardman’s schools at Tavoy.”[41] She “was in the habit of conducting a prayer-meeting of the female members of the church every week, and also another meeting for the study of the Scriptures. Her acquaintance with, and attachment to, the Burmese Bible was rather extraordinary.”[42]

Adoniram and Sarah were married for 11 years and birthed 8 children during their time together. Judson would affirm the linguistic abilities of his second wife by writing “there is scarcely an individual foreigner now alive who speaks and writes the Burmese tongue as acceptably as she does.”[43] Sarah excelled as a scholar and a mother.

CI-2595. A Karen baptism with George Dana Boardman on his deathbed and wife, Sarah, attending him.

Fifteen years before his death, Judson was described by a visitor thusly: “His age is but forty-seven; his eye is not dim; not a gray hair shows itself among his full auburn locks; his moderate-sized person seems full of vigor; he walks almost every evening a mile or two at a quick pace; lives with entire temperance and regularity, and enjoys, in general, steadfast health.”[44] In spite of his public persona, Judson was feeling the ravages of a life lived in sub-tropical Burma.

+++++++++++++++

Consistency rather than crises for Adoniram Judson and the modern missionary movement from America

The last 15 years of Judson’s life were a time of reasonable stability and harvest in his vocational calling. The Baptist Board sent both human and financial resources, which were dependable, though never enough. British protection and growing celebrity in the American media, positioned Adoniram Judson as a major player on the world stage.

On July 20, 1838, Judson would exult that he “had the happiness of baptizing the first Toung-thoo that ever became a Christian. I hope he will be the first-fruits of a plentiful harvest. God has given me the privilege and happiness of witnessing and contributing a little, I trust, to the conversion of the first Burmese convert, the first Peguan, the first Karen and the first Toung-thoo. Three of them I baptized. The Karen was approved for baptism; but just then, brother Boardman removing to Tavoy, I sent the Karen with him, and he was baptized there.”[45] Biographer Francis Wayland affirmed these aspirations in Judson when he opined, “He was ever striving to do what others had not done, or could not do. Every where it was his aim, though always by honorable means, to be the first.”[46] One of the many biographies of Judson centered its story on his desire to be the first—first in accomplishing things for God.[47]

CI-2635. Five locals with spears sitting on a riverbank above the elephant at work.

In March 1839, Judson continued to battle for his health but seemed to be losing the use of his voice. He stated that he had come to resign himself to his condition in God’s providence:

I had been subject to a cough several months, and some kind of inflammation of the throat and lungs, which, for a time, almost deprived me of the use of my voice;….It is a great mercy that I am able to use my voice in common conversation without much difficulty; but when I shall be able to preach again I know not. The approaching rainy season will probably decide whether my complaint is to return with violence, or whether I am to have a further lease on life. I am rather desirous of living, for the sake of the work and of my family; but He who appoints all our times, and the bounds of our habitation, does all things well; and we ought not to desire to pass the appointed limits…

And later the same year he again reflects:

I am in my fifty-first year. I have lived long enough. I have lived to see accomplished the particular objects on which I set my heart when I commenced a missionary life. And why should I wish to live longer? I am unable to preach; and since the last relapse, the irritation of my throat is so very troublesome that I can not converse but with difficulty…[48]

Judson would live eleven more years, but oral communication would be a problem for the rest of those years.

+++++++++++++++

Judson’s Burmese Dictionary

Because his voice was slipping and he could no longer effectively preach, Judson acquiesced to a task the Board had placed in front of him years before. On April 17, 1843, he wrote, “I am chiefly occupied in the Burman dictionary, at the repeated suggestion of the Board.”[49] He had finished the Bible translation in 1834, with the full document in print by 1840. Additionally, Judson had a series of tracts in circulation throughout Asia in Burmese, Karen, Pali and other languages.

The Triennial Convention’s Board had directed Judson to codify his vast knowledge of Burmese into a dictionary for the use of future missionaries. Late in life, Judson agreed and saw the dictionary as a “causeway, designed to facilitate the transmission of all knowledge, religious and scientific, from one people to the other.”[50] He worked on the dictionary from English to Burmese, and later from Burmese to English, until his death in 1850. Besides the translation of the Bible and the establishment of a church, Judson would identify the dictionary as the third great objective of his calling. The Judson Dictionary is still in print and used in Myanmar today.

+++++++++++++++

Sarah Hall Boardman Judson dies

Though the word “furlough” was not used in 1845, Judson and his wife Sarah Hall Boardman made a trek back to America to preserve Sarah’s health and deposit three of their oldest children in the U.S. for formal education. It had been 33 years since Judson departed America as a pioneer missionary. However, on the way back to the States, on September 1, 1845, Sarah died and was buried on the island of St. Helena in the Indian Ocean.

She sleeps sweetly here, on this rock of the ocean, Away from the home of her youth,

And far from the land where, with heartfelt devotion She scattered the bright beams of truth.[50]

A pew from Sarah Hall Boardman Judson’s home church, a gift from Rosalie Hall Hunt, now graces the upper north side of the Herrick Chapel at Judson University in Elgin, Illinois.

+++++++++++++++

Visit to the United States, 1845-1846

Judson was overwhelmed when he arrived in America in October 1845, and learned of his renown. He had no idea how popular his name and his missionary efforts had become in his native country. Judson quickly assigned three of his children by Sarah, Abby Ann (b. October 31, 1835), Adoniram Brown (b. April 7, 1837), and Elnathan (b. July 15, 1838), to friends and family as surrogate parents.

As the first foreign missionary from America, Judson received many invitations to speak, but could only fill the most pressing opportunities due to the throat and esophageal problems he had battled for years. When he did speak publicly, he used an interpreter to project his whispered message to the back of the auditorium. Judson never felt comfortable with the stardom that grew up around his persona.

English had become his second language, with Burmese now his heart language. He wrote, “In order to become an acceptable and eloquent preacher in a foreign language, I deliberately abjured my own. When I crossed the river, I burned my ships. For thirty-two years I have scarcely entered an English pulpit or made a speech in that language.”[52]

Adoniram Judson arrived back in the United States for his only furlough the same year that a free state, Maine, and a slave state, Texas, were admitted to the Union. It was also the year that Baptists in the South withdrew from the Triennial Convention and formed the Southern Baptist Convention. The problem of slavery had been debated among Baptists for a decade but came to a head when a potential missionary who owned slaves was denied appointment. Two hundred ninety-three state Baptist leaders, representing over 365,000 Baptists in the South, met in May of 1845 at Augusta, Georgia, and formed the Southern Baptist Convention.

CI-2612. A sharp-looking, neatly-dressed Adoniram Judson, Jr. later in life.

On his furthest trip south during the 1845-1846 furlough, Judson spoke to a group of pastors in Richmond, Virginia, on February 8, 1846. In typical self-effacing style, Judson said,

I am only an humble missionary of the heathen, and do not aspire to be a teacher of Christians in this enlightened country; but if I may be indulged a remark, I would say, that if hereafter the more violent spirits of the North should persist in the use of irritating language, I hope they will be met, on the part of the South, with dignified silence.[53]

One hundred twenty years before Baptist pastor Martin Luther King, Jr. advocated non-violent social change, Baptist missionary Adoniram Judson, Jr. advocated a non-violent response to solving the nation’s racial divide.

+++++++++++++++

Marriage to Emily Chubbuck (aka Fanny Forester)

At a Christmas Eve gathering in 1845 in Philadelphia, Judson met Emily Chubbuck, a lady half his age, who was one of America’s premier female writers. Emily’s first major work, Charles Linn, or How to Observe the Golden Rule, was published in 1841. Writing under the nom de plume Fanny Forester, Chubbuck sold articles and stories to leading publications, including the Broadway Journal and Graham’s Magazine which was edited by Edgar Allan Poe. She received the unheard-of fee of $5 per page.[54]

Judson proposed to Emily in early 1846, only two weeks after their first meeting. They were married in June and traveled to Burma to resume their missionary calling. Emily told a friend, “I have felt, ever since I read the memoir of Mrs. Ann H. Judson when I was a small child, that I must become a missionary.”[55] She would spend the next four years beside Adoniram Judson fulfilling that missionary calling.

CI-2625 shows Emily Chubbuck and a native helper at left. The girl on the front row is daughter, Emily Frances Judson. The two lads at the back are Judson sons by Sarah Judson, Henry and Edward.

In 1847, Emily Chubbuck Judson gave birth to Emily Frances Judson, her only child to attain adulthood. Emily had promised Adoniram that she would write a biography of his second wife who was buried on the island of St. Helena. In 1848, Emily finished writing The Memoir of Sarah B. Judson and in 1850, the book was published.

+++++++++++++++

Death of Adoniram Judson, Jr.

Though Judson did not enjoy the task, he worked tirelessly on the dictionary through November 1849. Emily wrote to Abigail Ann, Judson’s sister in Massachusetts describing his work on the dictionary:

I remarked that during this year his literary labor, which he had never liked, and upon which he had entered unwillingly and from a feeling of necessity, was growing daily more irksome to him; and he always spoke of it as his ‘heavy work,’ his ‘tedious work,’ ‘that wearisome dictionary,’ &c., though this feeling led to no relaxation of effort. He longed, however, to find some more spiritual employment, to be engaged in what he considered more legitimate missionary labor, and drew delightful pictures of the future, when his whole business would be but to preach and to pray.[56]

But in November 1849, he caught a chill while helping Emily with a sick child and never recovered. He spent the early months of 1850 battling a fever and trying to regain his health. In April 1850, at age 61, Judson left his pregnant Emily behind and boarded the French ship, Aristide Marie, in Moulmain harbor to spend some weeks breathing salt air in the Indian Ocean. This was a standard remedy that Judson had successfully used for previous respiratory problems. Traveling with him were Panapah, a personal servant, and missionary colleague Thomas Ranney, who attended to Judson through the last days of his life.

Adoniram Judson died April 12, 1850, aboard the Aristide Marie while on a voyage in the Andaman Sea hoping the salt air would improve his health.

Judson seemed to know he would not return to Burma and talked with Ranney about life, death, and eternity while on this final voyage. He said in part:

I am not tired of my work, neither am I tired of the world; yet when Christ calls me home, I shall go with the gladness of a boy bounding away for his school….I feel so strong in Christ. He has not led me so tenderly thus far, to forsake me at the very gate of heaven. No, no; I am willing to live a few years longer, if that should be so ordered; and if otherwise, I am willing and glad to die now. I leave myself entirely in the hands of God, to be disposed of according to his holy will.[57]

At fifteen minutes past four on April 12, 1850, Adoniram Judson breathed his last breath and passed on to his eternal reward. A plank coffin was constructed and sand was placed in the box to make it sink below the waves. At eight o’clock that evening the crew assembled, the port door was opened and “…all that was mortal of Dr. Judson was committed to the deep, in latitude thirteen degrees north, longitude ninety-three degrees east, nine days after their embarkation from Maulmain, and scarcely three days out of sight of the mountains of Burma.”[58]

The Aristide Marie proceeded on its way to the Isle of France. Three weeks after the death of Adoniram, Emily gave birth to Charlie, who never drew a breath and was buried in Maulmain. Four months later, Emily learned of the death and ocean burial of her husband from a letter sent by a Presbyterian pastor in Calcutta.

After the death of Adoniram in 1850, Emily returned to the U.S. the next year with her daughter Emily Frances[59] (b. December 24, 1847) plus Henry Hall (b. July 8, 1842) and Edward[60] (b. December 27, 1844), two sons by Sarah. Emily compiled the materials on her husband’s life and served as the editor for Francis Wayland, Jr., President of Brown University, as he wrote A Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, D. D. This two-volume work published in 1853, has the artistic flair of Emily Chubbuck (Fanny Forester) and the literary precision of Francis Wayland. It remains the classic biography of the first foreign missionary from America. Emily died the next year of tuberculosis and is buried in Hamilton, New York.

There is no formal gravesite for Adoniram Judson, the father of foreign missions from America, but his wife, Emily, wrote that Adoniram could have no more “fitting monument than the blue waves which visit every coast; for his warm sympathies went forth to the ends of the earth, and included the whole family of man.”[61]

In the Baptist church in Malden, Massachusetts, is a marble tablet that reads:

In Memoriam

Rev. Adoniram Judson,

Born Aug. 9, 1788,

Died April 12, 1850.

Malden, His Birthplace.

The Ocean, His Sepulchre.

Converted Burmans, and The Burman Bible,

His Monument.

His Record is on High.

+++++++++++++++

The final report of 1850

In 1813, Judson set as his goals to translate the Bible into Burmese and build a church of 100 baptized converts, a rather bold undertaking for a 24-year-old upstart. The 1850 mission report testifies to 7,908 baptized Christians in 62 churches with 174 trained leaders. Two hundred years after the arrival of Judson in Burma, 2013, the Myanmar Baptist Convention reported 3,700 congregations with 617,781 members and 1,900,000 affiliates.[62] This is one of the largest Christian concentrations in Asia.

Most of the mission’s general education involved women teaching literacy and Adoniram providing theological education and practical training. Those mission schools, however, were excellent. An article in the Calcutta Review of 1847 reported:

Too much praise cannot be bestowed on the labours of the American Baptist Mission in the education department. Their schools are far superior in every respect to the government schools at Moulmein and Mergui, and are producing among the Karens very remarkable effects…by far the best schools were those maintained by the American Baptist Mission, a body with no material interest in the country, but none-the-less entirely devoted to the welfare of the people.[63]

CI-2531. An early map of Burmah and Siam showing the chief cities, rivers, mountains and unexplored areas.

Adoniram Judson married three wives, each of them unique, strong, and necessary to the advancement of the mission. He buried two of his wives, with the third living only four years after his passing.[64] Between them, they would bear 13 Judson offspring, of which only six would live to adulthood.[65] But the Judson Legacy captured the energies of the world and has gone far beyond his wives, his prodigy and his missionary work.

Endnotes

[1] Originally published in A Noble Company: Biographical Essays on Notable Particular-Regular Baptists in America, Volume 8, Edited by Terry Wolever. Springfield, MO: Particular Baptist Press, 2016, Pages 535-572, 626-632. Used with gracious permission of Particular Baptist Press.

[2] See Ian H. Murray, Revival and Revivalism. The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism, 1750-1858. Edinburgh, Scotland: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1996.

[3] Francis Wayland, Jr., A Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, D. D. (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, and Company, 1853), 1: 25.

[4] Ibid., 28.

[5] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson (New York: Anson D. F. Randolph and Company, 1883), 17.

[6] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 1: 79

[7] James D. Knowles, Memoir of Mrs. Ann H. Judson, Late Missionary to Burmah (Boston: Lincoln and Edmands, 1829), 42.

[8] Maybe $700,000 in 2023 terms.

[9] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 1: 102.

[10] Ibid., 105.

[11] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 55.

[12] John Piper, “How Few There Are Who Die So Hard! Suffering and Success in the Life of Adoniram Judson: The Cost of Bringing Christ to Burma.” Paper delivered at the 2003 Bethlehem Conference for Pastors, Bethlehem Baptist Church, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Desiring God Foundation, 2015.

[13] Courtney Anderson, To the Golden Shore: The Life of Adoniram Judson (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1956), 173.

[14] Ibid., 419.

[15] Quoted in Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 80.

[16] Ibid., 77.

[17] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 1: 184-185.

[18] Ibid., 185-186.

[19]This is the first line from A View of the Christian Religion, in three parts.

[20] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 125.

[21] Ibid., 110.

[22] Ibid., 130.

[23] Ibid., 132.

[24] Ann Hasseltine Judson, A Particular Relation of the American Baptist Mission to the Burma Empire: In a Series of Letters, Addressed to Joseph Butterworth, Esq., MP London (London: J. Butterworth and Son, 1823), 334 pgs.

[25] Ibid., 36.

[26] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 2: 399.

[27] “Extract of a letter from Rev. Dr. Judson to the Corresponding Secretary [Lucius Bolles],” in Thomas Baldwin, ed., The American Baptist Magazine (Boston: James Loring, and Lincoln and Edmands), 6 (1826), No. 12 (Dec.): 367.

[28] Edward Judson, The Life and Times of Adoniram Judson, pp 289-290.

[29] Piper, “How Few There Are Who Die So Hard!”

[30] Courtney Anderson, To the Golden Shore (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Press, 1956), 391.

[31] Angelene Naw, The History of the Karen People of Burma (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 2023) provides an excellent history of the Karen and their relationship with American Baptist missionaries.

[32] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 376-377.

[33] Ibid., 395.

[34] Maung Shwe Wa, Burma Baptist Chronicle, Book I, 125.

[35] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 381.

[36] Ibid., 381-382.

[37] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, D. D., 2: 318.

[38] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 405.

[39] Ibid., 399.

[40] Sarah sent her six-year-old son, George Dana Boardman, back to the U.S., where he would receive his education and become a significant leader in the Northeast as pastor of the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia from 1864 to 1894.

[41] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 400.

[42] Ibid., 452.

[43] Ibid., 445.

[44] Ibid., 417.

[45] Ibid., 422.

[46] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 2: 375.

[47] William N. McElrath. To Be the First: Adventures of Adoniram Judson, America’s First Foreign Missionary. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1976.

[48] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 423-424.

[49] Ibid., 440.

[50] Ibid., 440-441.

[50] Ibid., 457.

[52] Ibid., 446.

[53] Ibid., 475-476.

[54] George H. Tooze, ed. The Life and Letters of Emily Chubbuck Judson (Fanny Forester). Seven Volumes. Mercer, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009. This is a wonderful collection of all of Emily’s writings.

[55] Edward Judson, The Life of Adoniram Judson, 482.

[56] Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 2: 338-339.

[57] Ibid., 346.

[58] Ibid., 352.

[59] Emily Frances married Thomas A. T. Hanna who became a pastor in Connecticut. They had eight children, two of whom were appointed missionaries to Burma.

[60] Edward eventually become pastor of the Judson Memorial Baptist Church in New York City (named for his father) and would publish The Life of Adoniram Judson in 1883.

[61] Quoted in Wayland, Memoir of the Life and Labors of the Rev. Adoniram Judson, 2: 348.

[62] Patrick Johnstone, Operation World (Carlisle, U.K.: Paternoster, 2001), 462.

[63] Maung Shwe Wa, Burma Baptist Chronicle, Book I, 118.

[64] Stuart, The Lives of the Three Mrs. Judsons, 248. First published in 1851, this recent edition was edited by Gary W. Long.

[65] The best review of the Judson domestic life and legacy is Rosalie Hall Hunt, Bless God and Take Courage: The Judson History and Legacy. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 2005.